I AM AN ADDICT

Marilyn Aminuddin

Marilyn Aminuddin

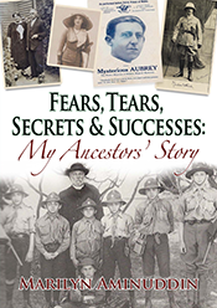

| Marilyn's book, the result of her genealogical journey | I am an addict! No, I am not addicted to alcohol, drugs or anything else illegal. I am a fanatic who searches for my ancestors. What began seven years ago as a hobby post-retirement, and a quest to discover more about my family has taken over my life. I need to know more, just as an addict needs his next fix. When I started on my journey, I knew next to nothing about my family other than a few basic facts. I was an only child, until at the age of sixty-six when I discovered that I had siblings; my mother was born in Australia as I was; my father came from England, and I knew there were Lithuanians lurking somewhere in the past. At the time, I could barely find Lithuania on a map of Europe. I also had no real inkling of what material might be available to me online. I only knew that as I lived in Malaysia and was not in a position to do any significant travelling, I needed the Internet to assist me in finding out more. In these last seven years, I have discovered all sorts of pitfalls which may arise in this sort of research and fell into a few genealogical traps and sink-holes from which I had to haul myself out. In this article, I will share some of these so that other researchers will not make the same mistakes. |

Multiple People with the Same Names

Very early on, I discovered that I had to be very, very careful to check and re-check materials which I found online relating to persons I thought were my relatives. A good example is my great-grandmother’s brother. His name was Jacob Bernstein. He was born in Schneidemühl, Posen, today called Pila, which is in the current borders of Poland, and migrated to Australia in 1854 at a time when the gold rush in Victoria had just begun. A huge number of Australian newspapers have been digitized and are available free at https://trove.nla.gov.au/search/category/newspapers/ and these became my basic source for information on the Australian side of my family. A search for Jacob Bernstein soon showed me that there were three Jacob Bernsteins living in Australia in the same period, although fortunately for me they were in different cities. “My” Jacob was in Ballarat, a gold mining town some two hours' drive today from Melbourne; another was living in Melbourne after having moved from New Zealand to Australia, and the third was in another state of Australia entirely. To make matters worse, my ancestor had a son Aaron who married Ivy Bernstein, daughter of the Jacob Bernstein in Melbourne! No doubt, at the time these families knew who was who, but 170 years later, I had to be very careful about checking and re-checking the information I was collecting.

Ignoring Historical and Geographical Data

| Sometimes, an inexperienced researcher who has no information from parents or grandparents to rely on looks at census and other life-recording records such as those from births, marriages and deaths. He may see that according to the records one person of interest was born in “Russia” but a supposed sibling was born in Poland. He then assumes that these two people cannot be brothers having been born in different countries. Oops! The Russia of today is not the geographical entity it was before World War One. Russia in the 19th century could refer to any number of modern countries such as Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova and so on. Thus, a researcher should be constantly reading the history of the shtetl, town, city or country which is of relevance to the family he is looking for. Such materials can explain so much about how our ancestors lived, why they moved and the issues they faced in order to find a better place to live. | The author visiting Telsiai, Lithuania, in 2022 |

Official Documents are the Truth, the Whole Truth and Nothing but the Truth

| The Re-purposed Telsiai Yeshiva, famous throughout Europe, visited by the author in 2022 | It is easy to fall into the trap of assuming that an official document is correct and reliable evidence about the person who is the subject of that document. Such reliance on documents is dodgy at best. Documents are only as accurate as the person giving the information. For example, dates of birth are provided on birth, marriage and death records as well as military enlistment records and travel documents. They may be accurate, they may not. I have found that my ancestors had decidedly fuzzy ideas about the year in which they were born. There is abundant anecdotal evidence to suggest that in Eastern Europe Jewish communities in the 19th century, many people did not know exactly when they were born. This seems very odd in the 21st century when we have to provide birth dates in order to acquire many essential records, including driving licenses and social security numbers. |

Where I live, everyone, including children over a certain age, is required to have a government-issued identity card, the number of which corresponds to one’s birth date (stated backwards). There is simply no way to fudge one’s age. A quick analysis of one line of my family who settled in Canada, after living a few years in England, and who later moved over the border, possibly looking for warmer weather, each had birth years which varied from one to five years in different records. At best, one could only say that a particular individual was born between x year an xx year. Birth dates can be inaccurate for other reasons than mere ignorance. For instance, a young woman migrating alone from Europe to the United States might fudge her date of birth on documents which needed to be shown to authorities for fear that she might be turned away at an entry port on the grounds that being so young she was vulnerable to exploitation, especially if the party she was expecting to meet her did not arrive or looked suspicious to the immigration officials. Also, as a person giving the information grew older, he might genuinely forget what age he had given officials for previous documents. Thus, in a series of censuses taken at 10-year intervals, a person might be x age in the first census in which he is listed; then 10 years later he is only 8 years older and in the next census he is now 13 years older than in the previous census.

After a while I realized that within a year or two it did not really matter when an individual was born. Instead of fussing about a date, I needed to ask about the person’s life. What was their occupation? Did they move from here to there? Were they involved in any activities to help others, and so on.

Relying on Online Websites

Getting basic information about an individual or family from online websites is a good place to start any research. Some are free and others require a subscription. I have found that beyond these sites, there are some wonderful Facebook groups whose members help others find their ancestors. Some tend to specialize in certain countries but there are also those which are international. The members are outstanding in the help they provide on a wide variety of matters, including translations, ideas on where to source information, discussions on common practices in Eastern Europe and elsewhere. There are many lively debates on the more controversial topics which are enlightening. As I have family in Australia, Canada, England and the United States, I have joined several of these groups and am amazed how members go beyond the call of duty in assisting those who post queries. Some of those who respond are recognized as experts in their respective fields and sit on the councils of genealogical societies and other organizations such as LitvakSIG and JewishGen.

There are also YouTube videos online, some of which are extremely helpful and interesting and others not so, but they are useful additions to a researcher’s toolbox and should be explored.

Although many others have given and continue to give the same warning, I think it is well worth saying that you should NEVER rely on other people’s family trees found on the various genealogical websites. Examine them and if they include people who you think may be connected to you, look for verification of the connection. Take these trees as a starting point and not as facts.

Expect a Long Journey

| Looking for information on our ancestors should be seen as a long-term project. It may well be stop and start, stop and start again. Life intervenes (which is why more retirees take up genealogy than youngsters). People with young children, busy work-lives and ill-health may have to retire from the genealogy scene at least for a while. Still, one should not give up entirely. The time will come when it may be possible to resume the journey in search of ancestors. For this reason, keeping a log is important. At the time of a discovery, you may think you will have no difficulty remembering where you found a nugget of information. Later, sometimes years later, you will not remember. Believe me, you will not remember. Of course, it is hard when information is flowing in and you are excited about your findings to stop and keep a log of where each piece of your family jigsaw puzzle was found. You may kick yourself later for your laziness when you are challenged to prove where some story or information came from, and you no longer remember the origins of the material. | Temple Court, Rectory Square, East End of London - first a synagogue, now an apartment block - the synagogue where my grandparents were married in 1896, six years after arriving in England from Lithuania. |

Keep in mind that new material and records are constantly being added to the various databases on the major websites, especially JewishGen and its allied sites such as LitvakSIG and JRI-Poland but also on ancestry.com and myheritage.com. Many nations are taking action to digitize official records and to make some of them available online. This process will undoubtedly continue and therefore every now and then it is sensible to re-visit sites that you may have previously checked out to see what is new.

Researching One’s Ancestors is Not Like Stamp Collecting

Collecting basic records to provide information such as place and date of birth, marriage, death and so on is a great start to building a family tree. But, if that is all you do, then I would describe you as being akin to a stamp collector whereby you are happy to see the collection get bigger and bigger with more and more albums neatly labelled but you know little or nothing about the background to the stamps in the albums. What was the event being celebrated on the face of the stamp? Who was the person on the stamp – why was he so famous that his face is printed on a stamp and so on. Similarly, in researching our ancestors we need to understand what was happening when a great-grandfather left Poland, or Prussia or Belarus at the time he migrated. Why did he leave? Was the journey easy or tough? What reception did he receive in his new home? Was he welcomed or did he find more of the same antisemitic behavior that he thought he had left behind? There are so many questions that need to be explored. I discovered that my great-grandfather, who left Lithuania in 1890-91, had a grandfather and two great-uncles all of whom were exiled to Siberia in 1849 and for whom no information is available after that date. Why were they exiled? Where were they sent in Siberia? What did they do in Siberia? So many questions which will probably never be answered satisfactorily. Perhaps one day, some new information or record will become available to provide answers.

Once an addict, always an addict. I shall not give up my quest to find out more about my family’s past. Who knows what I might find?

About the Author:

Marilyn was born in Australia, raised in New Zealand and has lived in Malaysia for over 50 years. Since retiring from teaching at the largest university in the country, she spends all her spare time researching her family history. Marilyn, using the professional name of Maimunah, is the author of several books relating to industrial relations, employment law and human resource management.

About the Author:

Marilyn was born in Australia, raised in New Zealand and has lived in Malaysia for over 50 years. Since retiring from teaching at the largest university in the country, she spends all her spare time researching her family history. Marilyn, using the professional name of Maimunah, is the author of several books relating to industrial relations, employment law and human resource management.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed